That little bit of exercise

Read the post here.

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

Madness and greatness

Read the post here.

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

Infographic on deadly disease

GOOD has an interesting infographic on deadly disease outbreaks throughout history. Though measles and smallpox are the most prolific microscopic assassins, claiming over 500 million lives, these diseases have been around forever -- measles since the 7th century BC, smallpox since 10,000 BC.

*Note: I've been using Google+ for a few weeks now, mostly as an intermediary between sharing a link on Twitter and writing a blog post. For the time being, I'm going to repost the content that generated a lot of interest. -BJM

GOOD has an interesting infographic on deadly disease outbreaks throughout history. Though measles and smallpox are the most prolific microscopic assassins, claiming over 500 million lives, these diseases have been around forever -- measles since the 7th century BC, smallpox since 10,000 BC.

What's more surprising to me is that the Spanish Flu killed up to 100 million people in just over a year's time as the 1918 flu epidemic spread.

Read the post on GOOD here.

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

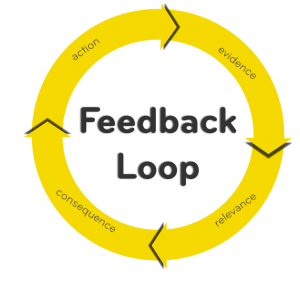

Meet the Feedback Loop

About a year ago, right after The Decision Tree book came out, I realized that a concept I touched on in the book had far larger potential. The Feedback Loop, it struck me, had potential as a framework for improving human behavior throughout our lives. Indeed, feedback loops could be put into action beyond health, into areas such as productivity, energy consumption, and other categories where human behavior plays a pivotal role.

About a year ago, right after The Decision Tree book came out, I realized that a concept I touched on in the book had far larger potential. The Feedback Loop, it struck me, had potential as a framework for improving human behavior throughout our lives. Indeed, feedback loops could be put into action beyond health, into areas such as productivity, energy consumption, and other categories where human behavior plays a pivotal role.

So it only took me 15 months, then, to tap out the article that is now the cover story in the new issue of WIRED: The Feedback Loop: How To Get Better At Anything.

This is a classic tech/trend piece, but one that I'm especially proud of, because I think it represents some thinking that goes way beyond my meager brain. It is, as much as anything I've ever written, very much in the zeitgeist in Silicon Valley. The idea is simple: Tracking our behavior can help us improve it. (This is the essence of the Quantified Self meetups that my pals Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly have curated). But the opportunity today is profound: New sensors can help us track our behavior more readily than ever before - and, moreover, that tracking can extend beyond the Silicon Valley crowd to the population at large. Feedback loops can be incorporated into all sorts of experiences and tools, and can be readily understood by all sorts of people. Thus, all of a sudden, a rather geeky idea starts to get rather universal. And that means SCALE, and that's where it starts to get interesting.

One thing I was sorry about in the Wired story was that I couldn't give full voice to the vast historical and contemporary context of feedback loops, exploring their roots in 18th century engineering and 20th century military strategy and contemporary philosophy and behavioral science. There is a HUGE amount to talk about in terms of feedback loops - where they come from, what they draw on, what they help us with today, and what they might enable tomorrow.

In other words, there's a lot more to say here. It's almost like there's another book in it....

Pork problems

Yesterday, Nathan Mhyrvold, an ex-Microsoft exec and all-around food nerd posted an excerpt of his new book Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking at The Guardian.

There, Mhyrvold talks about the “misconceptions of pork,” and how most of us cook the hell out of it, way beyond what’s needed to be safe. And for the most part, he’s right. In fact, the USDA just revised their standards for cooked pork, dropping the suggested internal temperature down from a cotton-mouthed 160 degrees to a succulent and juicy 145.

Yesterday, Nathan Mhyrvold, an ex-Microsoft exec and all-around food nerd posted an excerpt of his new book Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking at The Guardian.

There, Mhyrvold talks about the “misconceptions of pork,” and how most of us cook the hell out of it, way beyond what’s needed to be safe. And for the most part, he’s right. In fact, the USDA just revised their standards for cooked pork, dropping the suggested internal temperature down from a cotton-mouthed 160 degrees to a succulent and juicy 145.

Atop his soapbox, Mhryvold proclaims that naive American consumers and amateur cooks are so afraid of trichinosis that we nearly dehydrate our pork, lest we become stricken with such a dangerous pathogen. But our fears our misguided, he asserts, because an internal temperature of 145 is high enough to kill most microorganisms, and all the while trichinosis is becoming increasingly rare in domestic pigs.

And while that may be true, trichinosis in pork isn’t the problem, according to a survey highlighted by the Washington Post. Instead, consumers should be more cautious of toxoplasmosis, which infects 15-25% of seemingly healthy pigs in the US, and is the third leading cause of death when food illness is to blame.

Toxoplasmosis (which is spread by the toxoplasma microorganism) can be passed from an infected animal to humans when people consume undercooked meat. Roughly one-third of the global population is infected by toxoplasma (US infection rate is around 23% for people over the age of 12).

While most people infected by the parasite are completely asymptomatic, it is particularly dangerous to people with compromised immune systems, including pregnant women, where it can cause a host of issues as the baby comes to term. Taken together, the disease is the #2 most expensive food-borne pathogen, mounting a yearly economic burden of $1.2 billion.

I haven’t read Mhyrvold’s book. And so I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt, assuming this discussion is in there somewhere, but edited out of the online excerpt.

See the full list of the costs of food pathogens here.

Photo via Flickr / Boston Public Library

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

The rules of raw milk

As I start weighing the evidence for or against the raw milk movement, at least one thing seems clear: the government isn’t exactly friendly to the idea, as they mandate, and enforce, a lot of regulations in this space.

As I start weighing the evidence for or against the raw milk movement, at least one thing seems clear: the government isn’t exactly friendly to the idea, as they mandate, and enforce, a lot of regulations in this space.

Three months ago, NPR reported that the FDA was cracking down on a Northern California dairy farm that makes the wildly popular, high-end ($20 per pound) Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Company, an operation run by Jill Giacomini Basch and her sisters.

According to Basch, the sisters have never pasteurized their artisanal cheese, allowing it to keep a “farmy” taste (whatever that means). In the past, the FDA has stayed clear of the family's farm, because Basch followed their protocol: age unpasteurized cheese for 60 days to kill any E. coli bacteria that’s camping among its ridges.

But after two large-scale raw milk-related recalls, the FDA got spooked. They second-guessed themselves, mumbling about whether 60 days was in fact long enough to kill the harmful bacteria. And now many farm owners are holding their breath to see what the government’s new standards will be, and whether the changes will run them out of business.

The second interesting thing I found is that once federal hurdles have been cleared, purveyors still have to deal with their individual state governments. And it’s not just cheeses, or the raw milk enthusiasts, that are under scrutiny.

Last week, The Economist told the story of Homa Dashtaki, an immigrant whose family came to the US from Iran in 1984. Embracing the foodie culture of California, Dashtaki decided to make and sell her father’s secret family recipe yogurt, the type of craft food you’d expect to find in an outside stand of a farmer’s market.

Though Dashtaki’s recipe calls the same processed milk that one can get in a gallon jug in any supermarket, the California Department of Food and Agriculture told her that the state’s code requires that everyone producing yogurt must have the equipment that’s needed to pasteurize their product. She explained that she was already using pasteurized milk, but they didn't budge. Ultimately she gave in, conceding to their ridiculous requests. But the agency still wasn’t satisfied, because even with the equipment in hand, she would be re-pasteurizing pasteurized milk, which was also a violation of their antiquated rules.

So the rules prevent her from following the rules...yep, seems about right for government directives.

** Read post 1 here: So long, raw milk cheese **

Photo via Flickr / By DanBrady

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

The genetic sequence of dinner

The Associated Press reported today that a food distributor in Virginia will start tracking their beef from farm to table by monitoring a DNA tag. The technique has already been used in Europe, but people certainly have high-hopes for its utility in the US:

The Associated Press reported today that a food distributor in Virginia will start tracking their beef from farm to table by monitoring a DNA tag. The technique has already been used in Europe, but people certainly have high-hopes for its utility in the US:

[I]ndustry experts say being able to follow filet mignon, rib eye and other cuts of beef back to the ranch can pay off in multiple ways, including boosting consumer confidence, upping the value of a dinner, and cutting the time needed to track recalled meats.

And the company's market research backed their belief that people are willing to pay a premium for what they consider a "value-add" product:

Tests the company did in some steakhouses it supplies, as well as surveys outside other restaurants, showed consumers were willing to pay $2 or $3 more for the same cut meat if various “pleasers” were added — a higher quality of meat, traceability, as well as how the animals were treated and fed.

Any bets on how long until there's a tableside smartphone app tracing your dinner's journey? Or maybe showing at which restaurants the remaining portions of the cow are located? Then there could be a Facebook group that will bring the remote eaters...ah, forget it.

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

Unconventional investors

In the Bay Area, investors are a dime a dozen. Credentials for the job must come as part of the Successful Entrepreneur Gift Pack handed out after an idea nets a 9-figure payday.

Relax. I’m only (half) joking.

In the Bay Area, investors are a dime a dozen. Credentials for the job must come as part of the Successful Entrepreneur Gift Pack handed out after an idea nets a 9-figure payday.

Relax. I’m only (half) joking.

Investors are the lifeblood of the startup culture. But just because their numbers are strong doesn’t mean that getting even 30 seconds of their time is easy, as I found out first-hand while peddling my own idea a few years back. But I was one of the lucky ones. No, my idea didn’t get funded, but I was fortunate to have a few seconds of their time and make a pitch.

Some would view my experience as a failure. But as I see it, I met some of the brightest minds in the investing community, people who gave me honest feedback, and helped me figure out how to strengthen my proposal.

There’s an increasing trend where investors, both angels and VCs, are staffing their firms with people who have advanced scientific degrees -- PhDs and MDs. As a business-naive scientific mind, I found it often helps to have someone in the meeting room during the pitch meeting who chewed the same dirt that you did. No matter how skilled of a communicator you are, there will always be things that fall through the cracks as you try to convince the people with the money why your idea will revolutionize healthcare, medicine, or biotech. And I’m thinking that the advanced degrees in the room are there to not only prevent the investors from funding a project that doesn’t have legs, scientifically speaking, but to also make sure that a really sound idea doesn’t get lost in translation.

There’s a cool news update at Xconomy that talks about Milena Adamian, an MD/PhD cardiologist who’s been a venture capitalist at Easton Capital since 2007. Aside from her VC work, she was heavily involved in the earlier stage angel investing community since moving to the Bay Area four years ago.

But when she recently transferred to her firm’s NY office, she found the angel investing community she loved was non-existent on the east coast. So what does an investor who’s been in the thick of the Bay Area startup scene do when something she wants doesn’t exist? Damn right, she says screw it and forms her own company. Adamian now serves as the Director of her own angel investing forum, the Life Sciences Angel Network (LSAN), that operates in collaboration with the New York Academy of Sciences.

The idea of LSAN is to give NY-based life science entrepreneurs the fuel they need to get their ideas off the ground, at a time before most VCs would even shake your hand let alone hand you a single dollar bill.

Adamian is a facilitator. And in my mind that means that there's been times she's had to put lab rats born without a business bone in their bodies in their place, backhanding them for thinking ROI means Risk of Infection. And on the flip side, I'm guessing she's had to dropkick a penny-pinching, tightwad investor or two as they start thumbing through Wikipedia on their smartphone during a meeting to find out what in situ means.

Yeah, yeah, I know it’s easy for the formerly jaded scientist who now sits in the peanut-gallery roadside grandstands where the science and media information highways meet to say how great this initiative will be. But in all seriousness, with people flummoxed over the idea that we may be producing too many PhDs, it’s cool to see people pushing the bounds of what’s been considered “non-traditional” jobs for advanced scientific professionals.

Photo via Flickr / stevendepolo

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

So long, raw milk cheese

One of the biggest battles between strong scientific evidence and those with a downright pigheaded refusal to accept the facts isn’t happening inside a medical clinic, but in the dairy fields of Northern California.

One of the biggest battles between strong scientific evidence and those with a downright pigheaded refusal to accept the facts isn’t happening inside a medical clinic, but in the dairy fields of Northern California.

Nothing screams “Foodie” like being a self-proclaimed artisanal cheese connoisseur. Don’t believe me? Check out the lines of people stacked three deep at your local Whole Foods cheese counter on a Saturday morning, all waiting to get their fill of a distinctly bold raw milk cheddar. Trust me, I know what I’m talking about; I’m the one more than likely pushing my way to the front of the line.

Considering the numerous store recalls on tainted cheeses, study after scientific study showing that pasteurization is the most effective way to keep dairy products safe, and, um, I don’t know, the fact that I’m trained as a scientist, some of you will say that I should know better. And you’re right.

I know where the evidence points. I just don’t heed the advice. Well, I didn’t, until now. So, I’m swearing off raw cheese until I conduct a full investigation of what the risks include. (Happy now?) And instead of writing a monster post, I’m thinking I’ll make this into a series. That way, I can incorporate the feedback I get from readers along the way. Plus there are too many avenues to explore and I don’t feel like organizing the structure of a long post. (Yes, I’ve also developed a newfound zeal for brutal honesty, effective immediately.)

I think I know how this one is going to end , but it will still be fun to see what I learn. And who knows, maybe someone else has the same questions.

Photo via Flickr / Royalty-free image collection

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.

Measuring infectious disease

If the idea of triaging patients at the emergency room seems complicated, consider how public health officials prioritize threats posed by organisms they can’t even see. Yet the microscopic microbes and viruses that sicken millions of people with infectious diseases still require a plan of attack. As in any medical scenario, resources are limited. And whether it’s due to low staff numbers, not enough research dollars, or too few hours in the day, someone ultimately has to make the call on where to funnel assets. In 1994, the World Health Organization started measuring the cumulative healthy years lost to disease with Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY). And each infectious disease is currently ranked according to its DALY score, providing a numbered system to help guide the public health community in crafting a suitable approach to managing the myriad of diseases they face.

If the idea of triaging patients at the emergency room seems complicated, consider how public health officials prioritize threats posed by organisms they can’t even see. Yet the microscopic microbes and viruses that sicken millions of people with infectious diseases still require a plan of attack. As in any medical scenario, resources are limited. And whether it’s due to low staff numbers, not enough research dollars, or too few hours in the day, someone ultimately has to make the call on where to funnel assets. In 1994, the World Health Organization started measuring the cumulative healthy years lost to disease with Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY). And each infectious disease is currently ranked according to its DALY score, providing a numbered system to help guide the public health community in crafting a suitable approach to managing the myriad of diseases they face.

But a group of European researchers want to flip the system on its head. Their new method, instead of relying on observations and statistics calculated over the course of months to years, prioritizes infectious disease based on a quick search of scientific and medical publications. And according to a study they published in PLoS ONE, not only is their way faster, but it’s comparably accurate to WHO in identifying the latest trends.

The Hirsch index (or h-index) was created as a way to measure the impact a particular scientist has on his or her field. The value, h, represents the number of publications the researcher has with at least h other papers citing those works. So a scientist with an h-index of 10 has published that many journal articles which have been cited by 10 times a piece by others. It gives a reliable measure of a researcher’s overall value – and, let’s face it, feeds their ego better than standard measures of success, like publishing in top-tier journals.

By searching certain pathogen keyword terms, the team was able to adapt the h-index to score the impact of infectious disease. And as shown below, the two methods produced similar results. But the coolest part is that a single researcher complied h-indices for ~1,400 pathogens in 2 weeks’ time.

Granted, there are some limitations to the method described above, since no distinction is made between good and bad research articles, and emerging diseases may be ignored since they haven’t had enough time to generate a significant h-index score. But as I’ve discussed before, there is a clear trend of people working to bring public health data to light faster than before. It’ll be an interesting space to watch in the next few years.

Brian Mossop is currently the Community Editor at Wired, where he works across the brand, both magazine and website, to build and maintain strong social communities. Brian received a BS in Electrical Engineering from Lafayette College, and a PhD in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in 2006. His postdoctoral work was in neuroscience at UCSF and Genentech.

Brian has written about science for Wired, Scientific American, Slate, Scientific American MIND, and elsewhere. He primarily cover topics on neuroscience, development, behavior change, and health.

Contact Brian at brian.mossop@gmail.com, on Twitter (@bmossop), or visit his personal website.